Discovery of Wonder

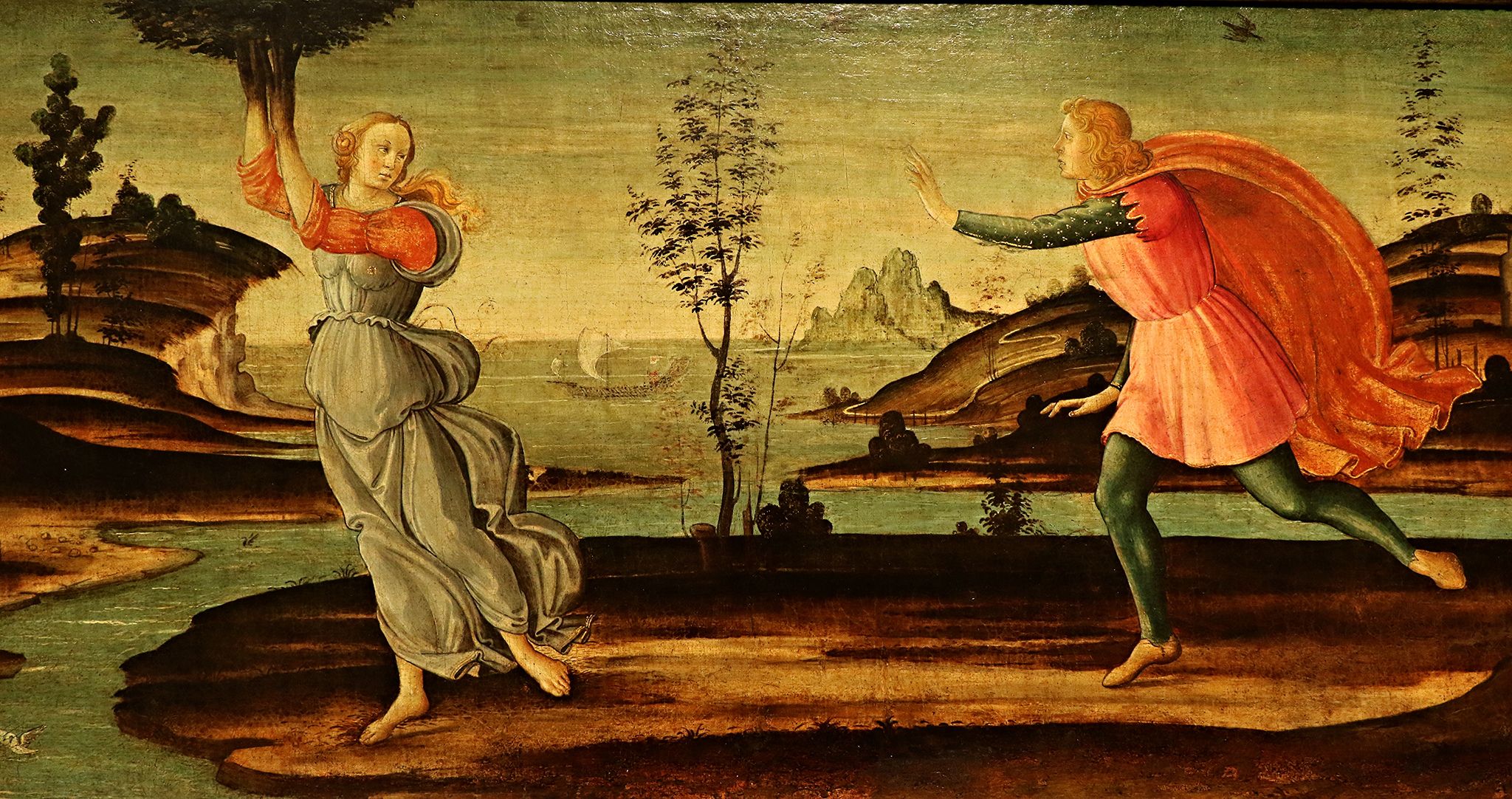

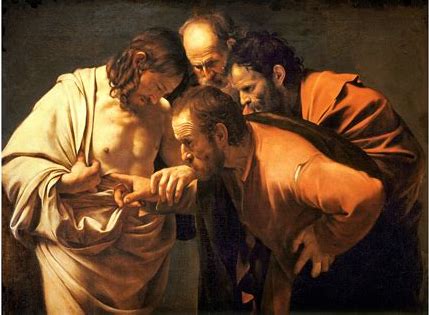

Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas

by Steve McDonald

In Caravaggio’s painting, Thomas’s brow

is furrowed, rough and weathered, of

rust-red tunic ripped at the shoulder, eyes

wide, stunned, unable to believe, though willing,

his leathery finger guided into the pierced,

pale flesh by the one he thought dead, the fold

of the open skin lifting up and out

as two disciples press in from the shadows,

bent by the soft light they lean into

Thomas’s other hand pressed against

his own side, as he also has been speared

and waits only for his own blood to begin

its steady flow. This morning on the patio

of a coffee shop, a girl with a yellow broom

sways in a slow overture of sweeping,

arms and hips moving to music of sun

and breeze as if she were the dance of the world.

I want to believe in such beauty.

I want to believe that whatever is wounded

can heal. In the pond in my yard, lily pads

float like paper hearts scissored from a child’s

bedtime story. Their stems vanish into dark water

from which, every so often, a flower blooms.

Discovery of Wonder

Routines run like clockwork, and we depend upon them for their predictability. When to sleep, when to wake, what to eat – these are natural habits, the core of the comfort we take in certainty. But much of our thought and ways of seeing can become habitual too, and limit the fullness of our capacity for sense experience.

Steve McDonald’s “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas” shares the title of a painting by Caravaggio. Because it was inspired by a work of art, it is called an “ekphrastic” poem. When reading an ekphrastic poem, you will be shown a detail or details of the art object, either all at once, or woven in. However, poetry doesn’t exist simply to be descriptive. Look for a transition, a movement away from the object and into the poet’s experience. In this poem, that shift begins in the fifth couplet:

. . . Thomas’s other hand pressed against

his own side, as he also has been speared

and waits only for his own blood to begin

its steady flow.

The signal phrase is, “he also has been speared”! How is that possible? Because the poem speaks about Thomas in figurative, not literal language. Just how has he been speared? Not with a sword, but with an empathic amazement he can feel in his side. This occurs in the real world, and is known as “empathic” or “sympathy” pain. (My mother had ALS, and I sometimes found it difficult to chew, or swallow.) From that point, the path of the poem takes a sudden turn, and we are on the patio of a coffee shop, an ordinary place that becomes a stage for something wonderful, if we have eyes to see it:

. . . a girl with a yellow broom

sways in a slow overture of sweeping,

arms and hips moving to music of sun

and breeze as if she were the dance of the world.

But the meaning doesn’t stop there. The poet makes a kind of confession:

I want to believe in such beauty.

I want to believe that whatever is wounded

can heal.

These words of desire, not only for wonder, but for miraculous healing, acknowledge a common deficit. There is a tendency to have more confidence in the physical representation of things, than in their transformative power, which is the essence of wonder.

The poem doesn’t just leave us wanting. It teaches us to peer into what seems as ordinary as our own backyard, and to be ready for something wonderful to happen:

. . . In the pond in my yard, lily pads

float like paper hearts scissored from a child’s

bedtime story. Their stems vanish into dark water

from which, every so often, a flower blooms.

Have you made a close-by wondrous discovery?